LONDON — Only last year,

Imran Khan was casting himself as the savior of Pakistani politics: a playboy cricketer turned opposition leader who enjoyed respect and sex appeal, filling stadiums with adoring young Pakistanis drawn to his strident attacks on corruption, American drone strikes and old-school politics. When Mr. Khan promised that he would become prime minister, many believed him.

Now, though, Mr. Khan’s populist touch appears to have deserted him.

He led thousands of supporters into the center of the capital, Islamabad, a week ago in a boisterous bid

to force the resignation of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, whom he accuses of election fraud. But the crowds he attracted were much smaller than his party had hoped, and the protest movement has been messy, inchoate and inconclusive.

Mr. Khan, 61, delivers speeches every day from atop a shipping container opposite the Parliament building, while his supporters sleep on the streets of a paralyzed city. But because he lacks the clout to break the political deadlock, he has turned to inflammatory tactics.

In recent days, he has called for a tax boycott, threatened to have his supporters storm the prime minister’s house, and pulled his party’s lawmakers from Parliament. In interviews, he has compared himself to Gandhi and to Tariq ibn Ziyad, an eighth-century Islamic general. In speeches, he has threatened his enemies and taunted Mr. Sharif, at one point challenging him to a fistfight.

The rest of the political opposition and much of the news media in

Pakistanhave turned against Mr. Khan, who is seen as having disastrously overreached. “Go Home Imran,” said a politically conservative newspaper, The Nation. Another writer called him “the Sarah Palin of Pakistan.”

But many worry that Mr. Khan’s brash tactics could endanger the country’s fragile democracy. Breaking its sphinxlike stance, the military intervened in the turmoil on Tuesday, urging politicians to resolve their differences with “patience, wisdom and sagacity.” Though benignly worded, the statement caused anxious flutters among the political class, who note Pakistan’s long history of military coups.

The protests in Islamabad “threaten to upend the constitutional order, set back rule of law and open the possibility of a soft coup, with the military ruling through the back door,” the Brussels-based International Crisis Group warned on Thursday. Hours later, the American Embassy in Islamabad said pointedly in a statement that its diplomats “strongly oppose any efforts to impose extraconstitutional change.”

On the streets, Mr. Khan’s movement has the boisterous feel of a midsummer music festival. Pop stars introduce his speeches, which are punctuated by songs during which his supporters, many of them women, burst into dance. A disc jockey known as DJ Butt is part of his entourage.

But Mr. Khan’s stewardship of that exuberant crowd has seemed erratic. When the marchers arrived in Islamabad on Aug. 15 after a punishing 36-hour journey from Lahore, the capital was being pounded by rain. While his supporters slept on the wet streets, Mr. Khan retreated to his villa outside the city to rest, drawing sharp criticism.

In speeches, he has used extensive cricket analogies, referring to himself as “captain,” and his heated, often intemperate style has alienated some supporters. At one point, he threatened to send his political enemies to the

Taliban so the insurgents could “deal with them.”

Mr. Khan’s call for supporters to stop paying taxes and utility bills met with widespread derision because few Pakistanis pay income taxes, and the country is already crippled with power shortages. His attack on the United States ambassador, Richard G. Olson, was seen as pandering to anti-American sentiment. “Are we, Pakistanis, children of a lesser god?” he said in that speech.

The protests stem from accusations of vote-rigging in the

May 2013 general election. Mr. Khan accuses Mr. Sharif’s party of fixing the vote in a number of constituencies in Punjab Province. Critics of Mr. Khan call his accusations sour grapes: Although international observers noted some irregularities, the election was accepted as broadly free and fair.

Suspicions that the military, whose relations with Mr. Sharif’s government have been tense, might have something to do with Mr. Khan’s protest movement were heightened by the appearance of Muhammad Tahir-ul Qadri, a mercurial cleric whose parallel movement has, in recent days, outshone Mr. Khan’s.

Mr. Qadri, who wants to replace Mr. Sharif’s government with one of technocrats, appears to have attracted a larger and more disciplined crowd, and to be benefiting from a simpler message. Normally based in Canada, he controls no seats in Parliament, and his populist manifesto is filled with laudable but vague notions like an end to terrorism.

Mr. Sharif’s government, which

initially reacted to the protests in a clumsy and sometimes brutal manner, has taken a more sophisticated approach in recent days. The police have allowed Mr. Khan’s and Mr. Qadri’s supporters to reach the area outside Parliament, although the building itself is surrounded by hundreds of soldiers.

On one level, the dispute is about control of Punjab, Pakistan’s most populous province and Mr. Sharif’s political heartland. Mr. Khan’s party, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, knows it must challenge Mr. Sharif in Punjab to stand a chance of beating him nationally.

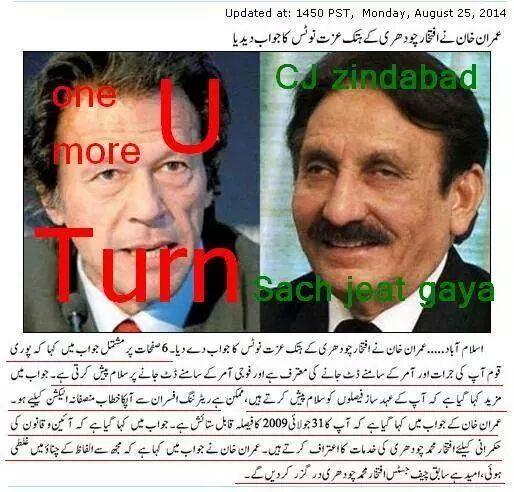

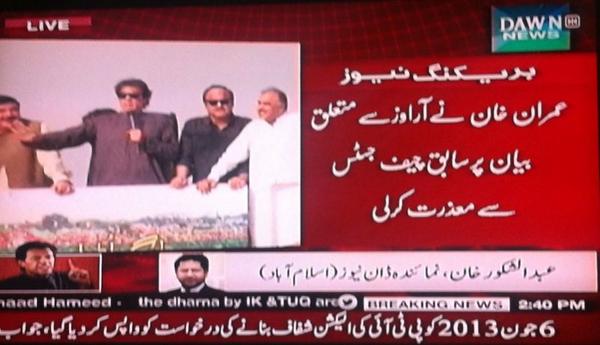

Negotiations started Wednesday, but Mr. Khan called them off a day later, demanding that Mr. Sharif resign first. Addressing a crowd, he railed against the prime minister in language considered coarse even by the rowdy standards of Pakistani politics.

Pressure to resolve the crisis is rising, both from hard-liners in Mr. Sharif’s party and from residents of Islamabad, who complain about the strain the protests have put on the capital. Protesters dry their laundry on the lawn of the Supreme Court and slip behind bushes to defecate.

The former president, Asif Ali Zardari, has offered to help mediate between the parties and met with Mr. Sharif on Saturday. But the situation on the streets remains fluid. An outbreak of violence or an overreaction by the police could shift the advantage to Mr. Khan and endanger the government, analysts say.

Few Pakistanis believe that a military coup is imminent. But the crisis has weakened Mr. Sharif, who has squabbled with the generals over policy toward India, peace talks with the Taliban and the fate of the former military ruler Pervez Musharraf, who faces

treason charges.

“The military doesn’t need to impose martial law now,” said Amir Mateen, a political analyst based in Islamabad. “Imran has weakened the entire political class, and the government is on its knees. The military can have its agenda fulfilled without doing anything.”

The next move, though, is up to Mr. Khan, who, having played an ambitious game, now needs to find a way to end it peacefully.